Redbrick Maintenance with Nomad

Hello there, (all together) General Kenobi!

Welcome to the latest edition of the admin blog. Today I’ll be running through how Redbrick has transformed itself from a hard to maintain, obscure and generally nuanced collection of hardware, into an almost fun cluster of servers to administer the systems of.

A Short View Back to the Past

4 years ago, Nikki Lauda said… rebuild a NixOS, it will rebuild with no issues. This year, James Hackett bought ihatenixos.org.

NixOS started as a fantastic idea for Redbrick. It put all of Redbrick’s configuration into source control, meant that changes could be reviewed before deployment and more. It meant that anyone could contribute to it, if they understood how it worked. And that’s where it failed. NixOS is a great idea, I’ll admit it. It has repeatable builds by design. It’s entirely declarative, great for running huge fleets of machines. However, for a student society, it was not the best choice.

The work done behind the scenes to get it working was immense, documentation was created out of thin air, knowledge was passed on. However, the intricacies of managing a non-standard (not Debian based) distribution of Linux meant new admins had to work extra hard to not only understand how to fix a problem, they also had to fix it in an environment they’re not comfortable in. The curve was way too steep. On more than one occasion it actively worked against us when trying to solve the problem because of how locked down everything was.

Downtime of old followed a simple formula: there will be downtime, it will start at this time and we will tell you when it’s over. We set no expectations because we’re all students and if you’re expecting a student society to have 4 9s of uptime, you might want to rethink your stance.

However, days of downtime were not uncommon. A service might break one day and we would carry on with it broken (sorry IRC), never really trying to fix it, because the underlying operating system was almost hostile to change. Alongside NixOS there were also file permission issues because of NFS, weird networking abnormalities and so much custom and “one time” fixes applied to things that navigating it was like going through the labyrinth, setting off a trap at every turn.

Dependency on dependency on dependency, weird cron scripts in random places dropping entire databases (sorry MPS), mailman issues (read about that adventure here) caused by migrations to python3 during a system upgrade, so many weird, wonderful and utterly soul destroying problems.

You can see why at the first opportunity I approached C&S with the notion of acquisition of new hardware - servers, switches and firewalls, disks and cables, to name a few pieces of the hardware refresh. The hellscape of “special” boxes and “you can’t do that because this’ll happen which has no apparent relation” would drive anyone to insanity, or retail therapy in this case.

I’ll give a talk on how Aperture came to exist in the near future. If I remember I’ll come back and link it here.

Now, let’s see how the recent downtime went…

Nomad’s Part to Play

Downtime in the world of Aperture is a joy to perform. A combination of ansible playbooks, job schedulers (in the form of Nomad) and an ultimately simple network topology leads to procedural maintenance plans that almost generate themselves.

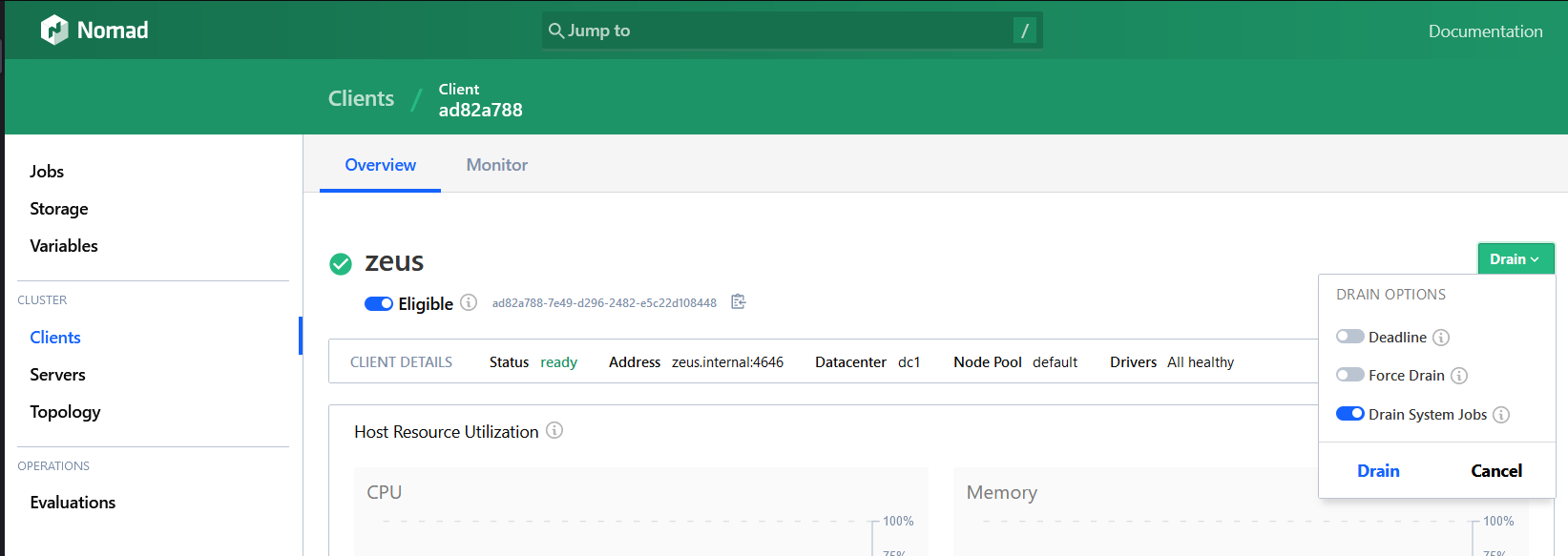

To start, we can “drain” Nomad clients. This essentially empties the node of allocations, and can mark the node as ineligible which tells the scheduler to not place anything on it. This means that all of the jobs are stopped gracefully on the node and can be replaced almost instantly on another client, meaning a service is stopped for roughly as long as a docker container takes to start.

Once the drain has been completed, we can then look to performing our changes to the host without fear of any extra downtime or data corruption to the jobs. In this instance, we upgraded the Nomad and Consul binaries on one host at a time. Once we had completed the apt upgrade, we could comfortably make the node eligible for allocations again and move on to the next host, repeating the same process.

In this way, given we have enough compute to run all of our jobs on the remaining nodes (and there are no extra constraints listed), downtime is minimised to almost nothing, even if a problem arises on one of the hosts.

The freedom and peace of mind this gives cannot be understated. Imagine you knew you could rely on Dublin Bus to always be at the bus stop when you expect it to be, without fail, or if it’s not there, there’s a very clear and obvious reason why it’s not there. Far fetched? Definitely - but not unachievable.

Downtime cannot be completely minimized in a few instances though. Moving the Bastion VM takes a little longer because of the nature of virtual machines and how quickly they spin up. It means that anything relying on ingress provided by the Bastion (see: web and Minecraft at the time of writing) will be interrupted. Luckily, restoring service is relatively easy. Backups of the qcow2 file can be served on a simple webserver for the Nomad client to download, and subsequently start. As the image was copied from a node that is connected to Nomad, starting the image back up will reconnect to Nomad also.

[!NOTE]

Note for Admins: When modifying the host that contains the Bastion VM, it’s advisable to drain the virtual machine first, then come back to the parent client and drain it. It will ensure that Nomad doesn’t mark the Bastion VM as “down”, rather than illegible. Any allocations on the Bastion VM will then also be placed as soon as it comes back online with little to no delay.

You Mentioned Ansible, What is That?

Imagine you wanted to upgrade packages on your Linux machine or WSL or similar. You probably have one or two steps you follow. They might look like this:

apt update- update the local package cacheapt upgrade- actually go and replace the local version with an up to date one

These two steps are pretty good to do, and usually every single time you want to update your packages you perform these two commands. Now, let’s say you have 5 servers to manage, you might write a little script that connects to each server with ssh and runs the two commands, or you might use something like parallel-ssh. All of these are well and good, but they lose their portability very quickly. Enter, Ansible.

Ansible is like a bash script that uses ssh on steroids. It uses yaml to inform the steps it should take (the apt update and apt upgrade from above) and pulls information about what hosts or servers it should affect from a dynamic or static inventory file.

The inventory file contains the connection instructions (and sometimes some facts) for ansible to connect to a server. Below is an example.

glados ansible_host=10.10.0.4

wheatley ansible_host=10.10.0.5

chell ansible_host=10.10.0.6

johnson ansible_host=10.10.0.7

[all:vars]

ansible_user=mojito

[nomad]

glados

wheatley

chell

The above “inventory” file is pretty basic, but conveys the majority of what you need to know. In this file, nodes (servers, virtual machines) are defined by default in the all group. Each one has a custom fact attached to it, specifying what the local address of the node is. The all group also has a set of variables attached to it, specifying the connecting user.

You can break nodes into further groups by specifying a nomad group for example, and placing the hostname, address or FQDN of the node under it. Custom groups can also have variables attached to them for more granularity.

TL;DR?

Fine, fine.

In summary, scheduled maintenance and downtime has become a whole lot easier to plan, execute, and tidy up afterwards. Given no network failure, we can essentially limit downtime of services to approximately the time it takes a virtual machine to start for single host maintenances. Larger maintenances will definitely have a wider margin, but baby steps.

It’s certainly a damn sight better than whatever we had before.